Karst. It’s a word that is almost synonymous with the Ozarks. Ask any self-respecting geographer to name one topographic feature within our area and chances are good that they will answer with that word. Ironically the word itself originates from the German word for a zone between modern-day Italy and Slovenia. “Karst is an area made up of Limestone…a soft rock that dissolves in water,” National Geographic informs us. As rainwater seeps into the rock, it slowly erodes, creating underground chambers and passages. Karst topography is known for unique features such as caves, underground streams and sinkholes, as well as the steep rock bluffs we associate with the James and other Ozarks rivers.

Recently I visited Devil’s Well along the Upper Current River near Akers Ferry. One of the most striking karst features in the Ozarks; it’s also one of the most fortunate, given its protection by the National Park Service. Like similar features, Devil’s Well is connected to the river by an underground lake called Wallace Well, near the well-known Cave Spring, which is visited by thousands every year who float the Current. Cave Spring was even the subject of a painting of the renowned Missouri artist, Thomas Hart Benton. Thomas Beveridge’s Geologic Wonders and Curiosities of Missouri notes that Cave Spring’s daily flow can be as great as 50 million gallons, and that Devil’s Well is a major part of its “plumbing system”.

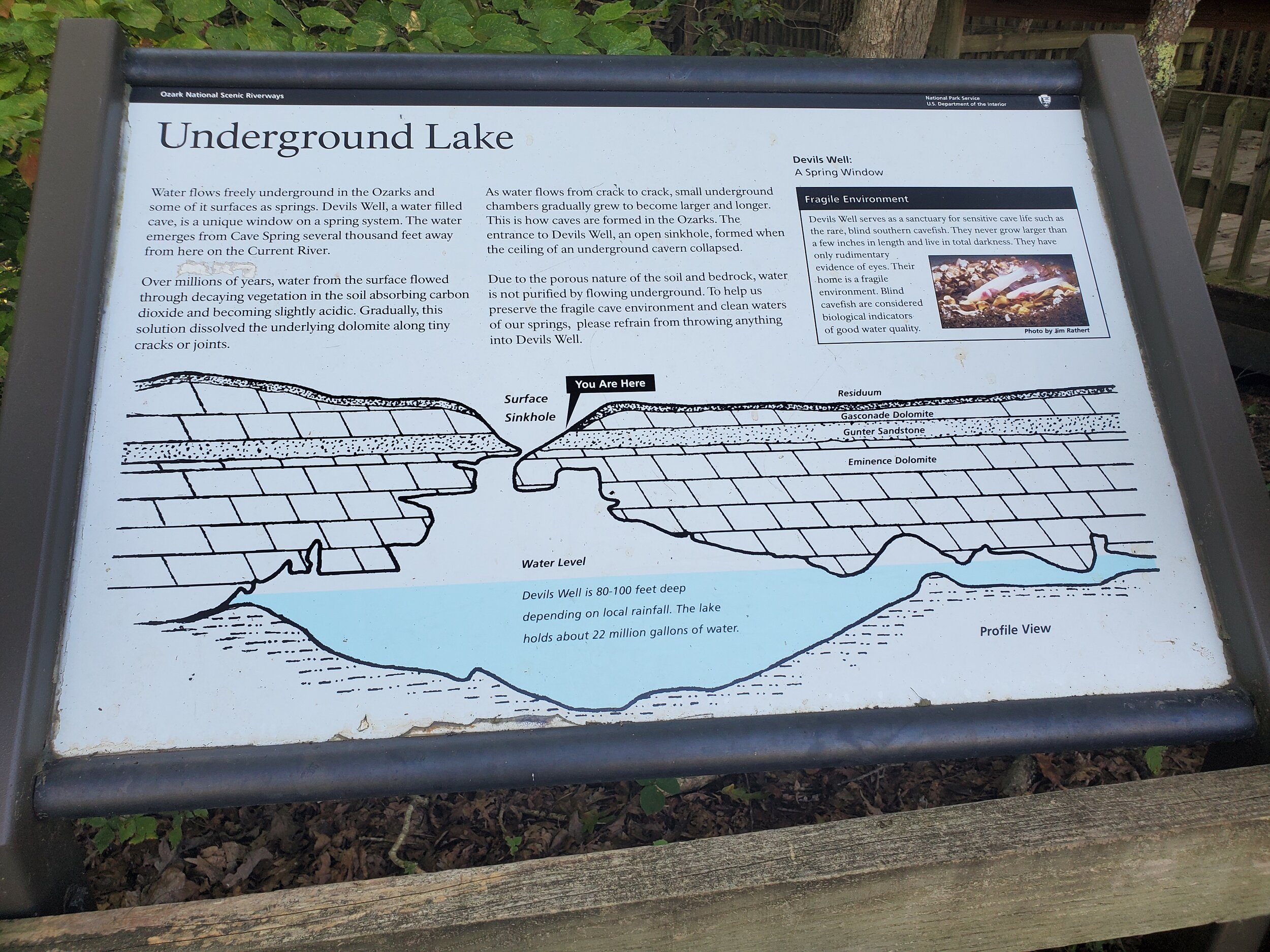

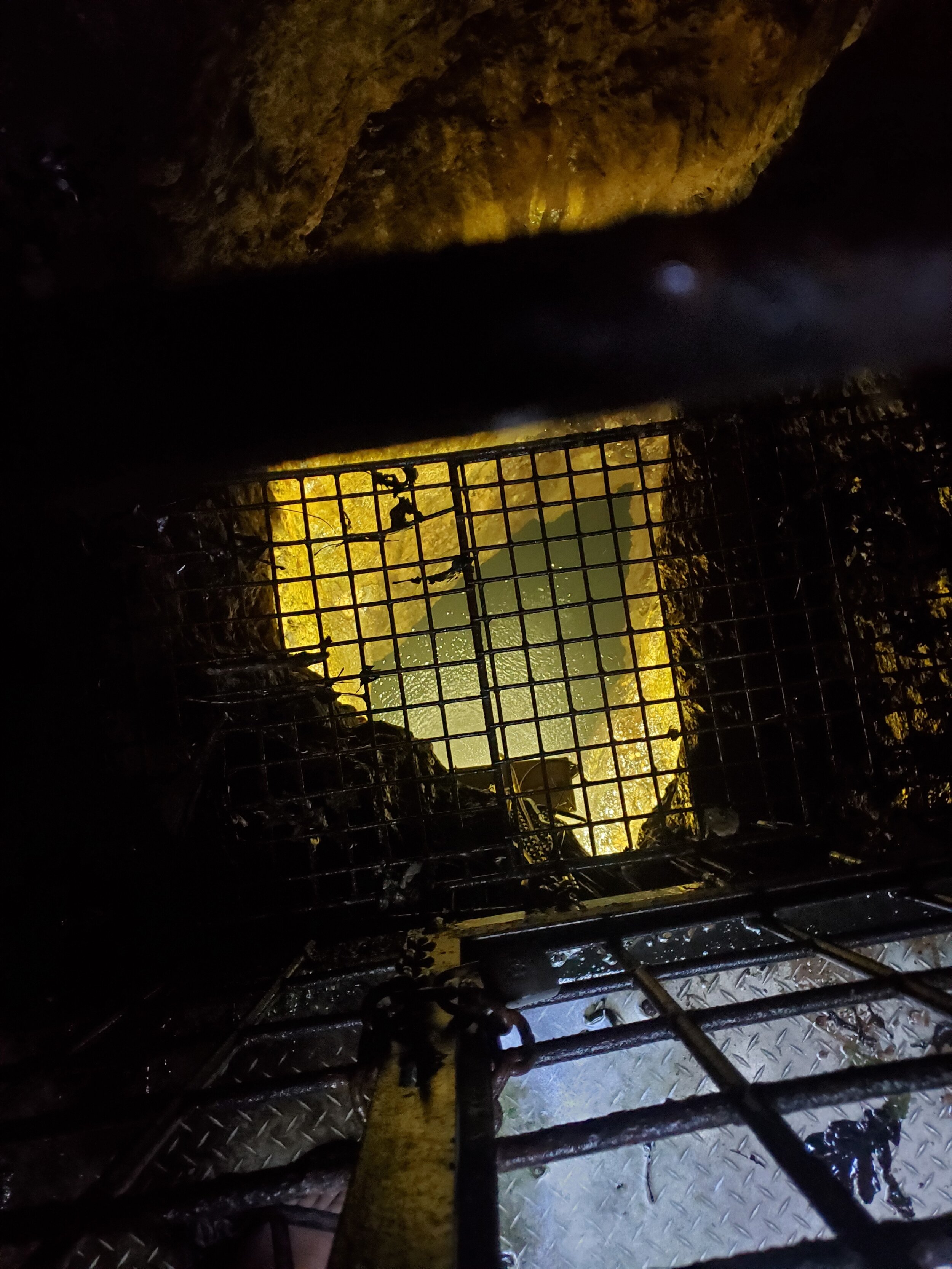

We arrived at the Devil’s Well after a bumpy drive down a county road and hiked from the parking area down a boardwalk built along the side of the giant sinkhole to a metal platform. A “karst window” in a caged area allows visitors to peer down into a giant chamber to view one of the largest underground lakes in the country, “more than 400 feet long and over 200 feet deep,” according to Loring Bullard’s newly published Living Waters: The Springs of Missouri. The Park Service notes that the lake holds about 22 million gallons of water. Looking down to the surface of the lake (with the aid of a motion-sensing light) made me almost dizzy.

Like many similar features in the Ozarks (Webster County’s Devil’s Den comes to mind), European settlers believed such places were entrances to the underworld. Vance Randolph documents several of them, complete with “furriners” throwing odd things from the escarpment and strange sulfuric smells and makes the tale of Devil’s Well an appropriate one for October and Halloween.

While early settlers of the Ozarks thought that subterranean chambers might be some sort of supernatural threat, today, the threat is to the karst features, as well as the surface and groundwater that plays such an important role in their formation. “Due to the porous nature of the ground, and the movement of water underground over sometimes great distances, groundwater in karst areas is particularly vulnerable to pollution,” states a National Park Service article, Caves and Karst. The blind cavefish that Vineyard noted living in the well are also the “canary in the coal mine” for water quality.

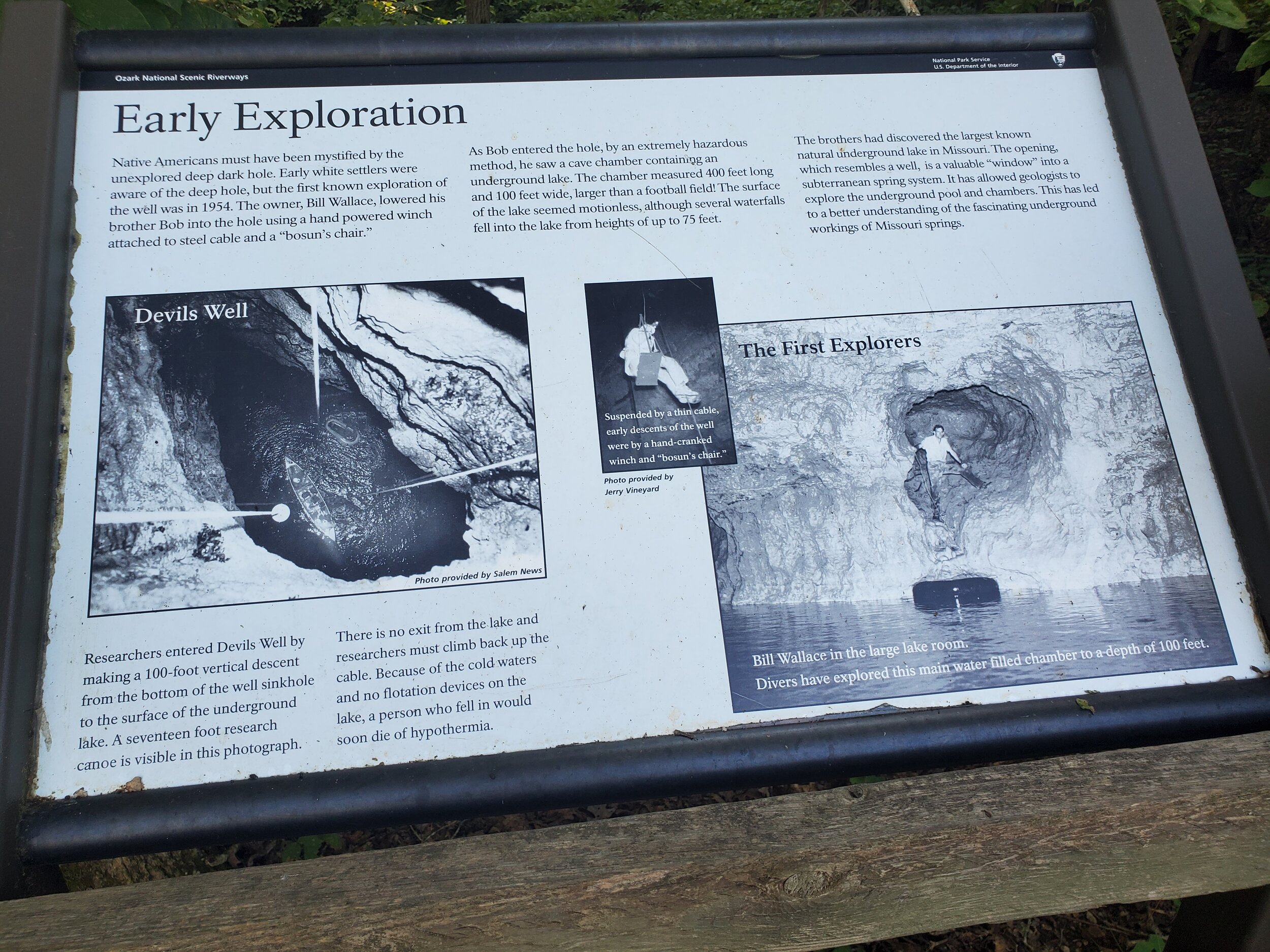

Devil’s Well was first mapped in 1956, when Jerry Vineyard descended a Bosun’s Chair (which is normally used to ferry personnel between ships at sea) to an aluminum canoe that had been lowered 100 feet to the lake below. Vineyard was there almost 60 years later in 2015 when divers and cave scientists made the dangerous journey to the well. A fall from the platform into the well’s icy waters below could result in hypothermia and death.

But the Upper Current isn’t the only place to see these geologic wonders; the James River basin, and especially the Wilson’s Creek watershed, with their own karst topography, is filled with similar features. Many of them are on private land, and not under the protection of government agencies, so it’s up to individual Ozarks residents to ensure that these windows into our area’s ground water system are protected from runoff & pollution.

That groundwater, in turn, feeds surface water such as Wilson’s Creek and the James through the numerous springs that dot our landscape. Streams and surface runoff do not have the chance to filter through the soil, and those pollutants can easily transfer to drinking water in wells and springs.

What should you do if there’s a sinkhole, spring or losing stream on your property? Planting a vegetative barrier, like a riparian corridor, will help create that last line of defense from runoff and sediment and protect water quality. Fencing off a sinkhole or spring to keep cattle and other farm animals out will help prevent erosion and deposition of bacteria and nutrients, all while keeping animals safe.

Through the Wilson’s Creek 319 Grant, JRBP is working to improve and protect vegetative corridors along our area streams through invasive species removal, tree planting and conservation easements. These same practices can be applied to lands near springs and sinkholes, which provide a direct connection to our groundwater. Don’t use a sinkhole as a dump for trash and debris, and don’t build on or around the rim of a sinkhole. And if you find a sinkhole where trash has already been dumped, consider organizing a litter cleanup.

For the earliest settlers of the Ozarks, sinkholes like the Devil’s Well were places of terror. Beveridge notes over 80 places in Missouri named for “Old Scratch” as the Scots-Irish pioneers called him. Yet for those of us who work in water today, it’s not so much the devil living at the bottom of the sink, but the threat to our ground and surface water from pollutants due to lack of “karst protection”. Sinkholes, caves and losing streams are literally a gateway to another world, and a fragile one that that. In that sense, we’re all the gatekeepers.

We’ll see you on the river.

Todd

Click on pictures to advance photos.